The Romano-Gaulish Woman’s Garments from Les Martres de Veyre: A Possible Reconstruction.

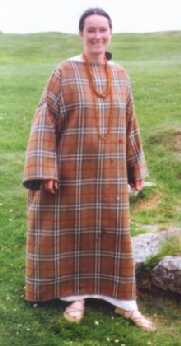

This project started with the aim of finding an archaeologically attested outfit suitable for outdoor wear, and handling livestock, in the unpredictable weather of the North of England. The Classical drapery styles are totally unsuited to these conditions and are inherently unlikely to have been worn by indigenous Romano-British rural women. One possibility considered was the tube dress, or peplos, style. A good example of this type survives from Huldremose in Denmark (Hald 1980, 360). Sleeves were, however, considered desirable so the wide, sleeved, tunic, referred to as the Gallic coat by Wild (1968, 168-70), seemed an appropriate garment for further consideration. Ankle length hem lines are not particularly suitable for wear where mud and manure abound, so a shorter skirt was also required.

Wild (1968, 169-70) used the remarkable find of a complete surviving Gallic coat from a woman’s grave at Les Martres de Veyre to illustrate his section on Basic Male Costume, acknowledging that while this find was strictly outside his core study area, it is the only complete garment known from the western provinces of the Roman Empire.

This unique find of a clothed female body appears to have been sadly neglected in other English literature on the topic. For example, much has been made of the comparatively recent find of a textile sock at Vindolanda (Goldman 2001a, 125). The Martres de Veyre body had knee length cloth stockings and this, or another, body had cloth slippers but Goldman makes no mention of these. In contrast Roche-Bernard (1993, 11-13) gives this find prime consideration in her discussion of female Gallo-Roman clothing.

This body was found in one of six graves discovered by chance during digging of brick earth in a quarry. Audollent (1921, 1922) published accounts of all six graves, labelling them Tombes A-F. This nomenclature has been followed by all subsequent authors. The first two graves, Tombes A and B, were uncovered in 1851 and little has survived from them. The remaining four graves, Tombes C-F, were discovered in 1893. Tombe D contained the Gallic coat. Audollent lamented the lack of either drawings or photographs, particularly of the 1893 finds, and the loss of information about the graves, and their contents, in the intervening years. The exceptional preservation of the garments, basket, fruits and other perishable organic materials in these graves is attributed to the presence of natural carbonic acid gas in the subsoil of the region. This unusual circumstance has preserved the different shades of brown of the Gallic coat, stockings and slippers, as may be seen in the colour postcard printed by the Mus¾e Bargoin, Clermont-Ferrand, where the garments are on display.

The body in Tombe D dressed in the Gallic coat was that of a young woman with a plait of bright blonde hair. Also on the body were the pair of cloth stockings, a pair of leather shoes and a girdle. Audollent attributes the cloth slippers to this body, because of the exceptional preservation of the find, but it is possible they belong with another of the 1893 graves, Tombe E, containing the body of a middle aged woman with a pair of sheepskin lined wooden pattens.

The body in Tombe D dressed in the Gallic coat was that of a young woman with a plait of bright blonde hair. Also on the body were the pair of cloth stockings, a pair of leather shoes and a girdle. Audollent attributes the cloth slippers to this body, because of the exceptional preservation of the find, but it is possible they belong with another of the 1893 graves, Tombe E, containing the body of a middle aged woman with a pair of sheepskin lined wooden pattens.

Audollent gives the dimensions of the Gallic coat as 1.25m in height, 1.7m in breadth with both arms extended, each sleeve being 40cm long. A conspicuous tuck, 8cm deep, has been made towards the middle of the garment with a double row of large stitches in white wool. The body of the garment has been made of one piece of cloth and there does not appear any appreciable difference between front and back. A girdle, 4.3m in length, including the fringes, and 12cm wide, was found on the torso but no clear account of the position or manner of wrapping it on the body was made. Audollent published good quality photographs, for the time, of these garments but no scale drawings. Fournier (1956, 203) published a very small scale drawing of the Gallic coat and stockings with patterns of both. Fournier shows sloping shoulders on the Gallic coat and this is also apparent in the photograph in the Mus¾e Bargoin guidebook (Ruiz no date). Neither Wild (1968, 171) nor Croom (2000, 137) show this detail in their drawings of the garment.

Hald (1946) and Wild (1968) have noted similarities in style and construction of T shaped garments from Scandinavia and Egypt, though of different fabric, respectively wool and linen. Of particular interest with regard to the Martres de Veyre Gallic coat is the central tuck or overfold seen on some of the Egyptian Coptic tunics. Roche-Bernard (1993, 11-12) suggests some possible reasons for this, primarily a desire to shorten the garment without leaving the marks and wear on the cloth associated with turning up a hem at the bottom. Having discovered all the published information about this particular Gallic coat, this style was considered to be appropriate for the required use. The next stage was making the garment. All the authors who have discussed this Gallic coat have given its dimensions and Fournier (1956), who seems to be the only person to have actually handled the garment since Audollent, gave the pattern. There is a slight taper on the sleeves as well as the shoulder. Although Fournier does not discuss this, it was thought unlikely that the cloth would have been cut to shape. Instead the seams were used to give the shape, without losing any cloth should the garment be unpicked for later re-use. This practice is known archaeologically but from a culture far removed in time and place (Wayland Barber 1999, 40). The cloth used for the reconstruction is some 4cm narrower than the original. This has led to a slight exaggeration in the finished garment of the slope of the shoulder seam, compared to the original. No precise description has been given by any of the authors who have considered this garment of how the wrists and hem have been finished. In the absence of clear pictorial detail, a decision was taken to adapt a technique illustrated by Audollent (1922, Pl. XI) on a surviving fragment from one of the 1851 finds, Tombe A which was also a woman’s grave. This shows a cord secured by whipping stitch to finish the edge. Several techniques of making simple cords exist. Although not positively attested for the Roman period, the woollen cord for this reconstruction was made with a lucet. Neither was the method of finishing the neck described. Here, the cloth was folded under, following the shoulder seam line, to give a straight opening, clearly depicted on Fournier’s pattern.

At this stage, the garment gave the appearance of the normal interpretation of an ungirt Gallic coat. It was comfortable to wear. Another costume topic was sparked off by plucking and drawing a chicken whilst wearing it and getting bloodstains on the new garment. Did people wear aprons in this period? There is abundant pictorial evidence for medieval women wearing aprons for all outdoor tasks but when did this practice become commonplace? Roussin (2001, 183) has a tantalising hint in the list of eighteen garments that a Jewish man was permitted to remove from a burning house on a Sabbath. This includes an apron but this word is not a transliteration of either a Greek or Latin word, unlike the words for the principal items of clothing.

At this stage, the garment gave the appearance of the normal interpretation of an ungirt Gallic coat. It was comfortable to wear. Another costume topic was sparked off by plucking and drawing a chicken whilst wearing it and getting bloodstains on the new garment. Did people wear aprons in this period? There is abundant pictorial evidence for medieval women wearing aprons for all outdoor tasks but when did this practice become commonplace? Roussin (2001, 183) has a tantalising hint in the list of eighteen garments that a Jewish man was permitted to remove from a burning house on a Sabbath. This includes an apron but this word is not a transliteration of either a Greek or Latin word, unlike the words for the principal items of clothing.

The next step was to add the central tuck. Fournier’s pattern clearly shows that this widens at the sides and narrows centre front and back. The same styling may be seen in the Egyptian Coptic shirt discussed by Burnham (1973, 10), who suggests this shaping would have made the bottom of the garment hang evenly when belted. The tuck was placed, as far as possible, in the position indicated by Fournier’s pattern. On trying on the garment, after this addition, the tuck turned out to fall at hip height, rather than waist height as had been anticipated, though with no actual evidence. This considerably altered the feel of the garment when wearing it. The addition of the tuck raised the hem line considerably, from originally ankle length to just below the knee. This is a commonplace in working women’s outfits of more recent eras (Cunnington & Lucas 1967) but is not normally associated with surviving pictorial evidence from the Roman period.

The girdle then had to be considered. As it survives today, the original find from Tombe D is in two unequal halves. While there is no proof, it was thought possible that the break might have occurred where the girdle was folded in two halves. A piece of commercial wool braid of comparable length, but some 9 cm narrower than the original, was used at this juncture but folded in half to give a more manageable length to deal with. Burnham (1973, 10) suggests that the girdle would have covered the tuck, hiding the seemingly rather crude stitching. Roche-Bernard (1993, 12) assumes that the girdle would have been worn at the waist, with many turns round the body and possibly blousing of the bodice. Both these options were tried and neither felt right. Instead, the girdle was tied under the tuck with a knot and bow at the side. This is easy to put on and very comfortable to wear. It gives the garment a rather 1920’s look. On the practical side it stops draughts, traps air in the very loose bodice which keeps one warm, and allows a great deal of freedom of movement for physical tasks. There is a pronounced tendency for the neck line to ride high at the front and droop behind. This is neither noticeable nor uncomfortable when wearing the garment.

The girdle then had to be considered. As it survives today, the original find from Tombe D is in two unequal halves. While there is no proof, it was thought possible that the break might have occurred where the girdle was folded in two halves. A piece of commercial wool braid of comparable length, but some 9 cm narrower than the original, was used at this juncture but folded in half to give a more manageable length to deal with. Burnham (1973, 10) suggests that the girdle would have covered the tuck, hiding the seemingly rather crude stitching. Roche-Bernard (1993, 12) assumes that the girdle would have been worn at the waist, with many turns round the body and possibly blousing of the bodice. Both these options were tried and neither felt right. Instead, the girdle was tied under the tuck with a knot and bow at the side. This is easy to put on and very comfortable to wear. It gives the garment a rather 1920’s look. On the practical side it stops draughts, traps air in the very loose bodice which keeps one warm, and allows a great deal of freedom of movement for physical tasks. There is a pronounced tendency for the neck line to ride high at the front and droop behind. This is neither noticeable nor uncomfortable when wearing the garment.

Most artistic representations of Classical dress show narrow cloth girdles, usually tied either or both under the breasts and round the hips (Bellido 1949, 139 Pl. 184). A broader cinching of the garments at hip level is depicted in the paintings of Jewish women in the synagogue of Dura-Europos (Roussin 2001, Fig. 11.6). Croom (2000, 130) describes this cinching as being an integral part of the draping of the mantle, not a separate girdle.

Most artistic representations of Classical dress show narrow cloth girdles, usually tied either or both under the breasts and round the hips (Bellido 1949, 139 Pl. 184). A broader cinching of the garments at hip level is depicted in the paintings of Jewish women in the synagogue of Dura-Europos (Roussin 2001, Fig. 11.6). Croom (2000, 130) describes this cinching as being an integral part of the draping of the mantle, not a separate girdle.

Linen does not normally survive in the same burial conditions that preserve wool, so it is not surprising that no trace of any linen textiles were found in any of these graves. However a linen undershift is normally worn under this reconstruction woollen garment for the practical considerations of an extra layer of warmth and ease of laundering. By the expedient of wearing the woollen garment without the linen undershift, it was found that the wide neckline tends to slide off one or other shoulder. This does not happen when it is worn over linen, a practical consideration in favour of wearing linen underneath.

Fournier (1956, 203) shows the stockings as being made in two pieces, a straight tube sewn centre back for the leg and heel with a curved cut out for the instep and a D shaped foot piece seamed under the foot and to the leg part. The tops of the stockings are fringed. No garters were found on the body but there is a suggestion that garters might have been threaded through below the fringe line. Fournier’s pattern was scaled up to fit. On the modern reconstruction of these stockings garters, again of lucet cord, are tied below the fringe and the fringe folded down to cover the garter. These stockings are extremely comfortable to wear and do not fall down if the garter is tied on properly. Worn like this, the fringed tops of the stockings are visible below the hem of the Gallic coat.

None of the authors who have discussed the garments from Les Martres de Veyre have given any details of the size or construction of the slippers. Indeed, it is not clear which of the two women’s graves, Tombes D and E found in 1893, contained them. This reconstruction has been based on the photograph published by Audollent (1922, Pl. X no. 3) and general similarities with Viking age shoes found at York (Carlson 2002). The slippers comprise a sole and a one piece upper. There is a long tab for fastening but the method of fastening is unclear. There appears to be no surviving toggle or loop. No-one seems to have considered whether these slippers were unfinished when placed in the grave or fastened by an organic material, such as linen cord or horn toggle, which has not survived. As a compromise, pending further information, these slippers are usually worn with the tab pinned in place with zoomorphic brooches. There may be no evidence whatsoever for this practice but the effect is attractive.

The shoes found with the body in Tombe D are of leather and obviously made by a professional. As such, it has been beyond the scope and budget of this project to have copies made. Instead, a simple pair of one piece, laced, sandals have been worn over the stockings. This combination is extremely comfortable and warm under average weather conditions. For wet weather, pattens have been worn in addition. For colder weather, the slippers have been substituted for the sandals, though the possibility exists that the slippers were worn over the shoes, in the manner of galoshes, though not waterproof. Since the original shoes have about 30 hobnails in the soles, such overslippers could have been worn to protect floors indoors too. This project has not yet reached the stage of lining the pattens with sheepskin, as evidenced from Tombe E. However, this combination of footwear indicates that a practical range of options was available for keeping the feet warm, dry and comfortable in the worst of weather.

No cloak or mantle was found with the body in Tombe D, though these are known to have existed at this time. The famous sculpture from Housesteads (Crow 1995, 72 Pl. 47) shows three figures in long hooded cloaks, which completely conceal the clothes worn underneath. Such a garment worn over the outfit from Les Martres de Veyre would probably provide adequate warmth and protection in winter for outdoor tasks. This archaeological evidence suggests there is no need to be cold and miserable when wearing period style clothing for outdoor work and demonstrations. While not endorsing Goldman’s (2001b, 213) acceptance of modern and synthetic fabrics, this project concurs that “Working out practical solutions to problems of constructing the ancient garments gave insights that became apparent once the fabric was cut, draped and sewn. There is no substitute for repeating the actual process of making the costumes to find out how they were constructed, and lessons were learned from each experience.”

References

- Audollent, A. 1921. Les Tombes des Martes de Veyre. Man 96, 161-4.

- Audollent, A. 1922. Les Tombes Gallo-Romaines ´ Inhumation des Martres de Veyre (Puy de DÛme). M¾moires pr¾sent¾s ´ l’Academie des Sciences et Belles Lettres 13, 275-328.

- Bellido, A. G. Y 1949. Esculturas Romanas de EspaÔa Y Portugal. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cient�ficas. Madrid.

- Burnham, D. K. 1973. Cut my Cote. Royal Ontario Museum

- Carlson, I. M. 2002. Footwear of the Middle Ages. www.pbm.com~lindahl/carlson/SHOEMHOME.HTM

- Cunnington, P. and Lucas, C. 1967. Occupational Costume in England: From the 11th century to 1914. A. and C. Black Ltd. London.

- Croom, A. T. 2000. Roman Clothing and Fashion. Tempus Publishing Ltd. Stroud.

- Crow, J. 1995. Housesteads. B. T. Batsford Ltd.

- Fournier, P.-F. 1956. Patron d’une robe de femme et d’un bas gallo-romains trouv¾s aux Martres de Veyre. Bulletin Historique et Scientifique de L’Auvergne 76, 202-3.

- Goldman, N. 2001a. Roman Footwear. In J. L. Sebesta & L. Bonfante (Eds) The World of Roman Costume. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Goldman, N. 2001b. Reconstructing Roman Clothing. In J. L. Sebesta & L. Bonfante (Eds) The World of Roman Costume. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Hald, M. 1946. Ancient Textile Techniques in Egypt and Scandinavia. Acta Archaeologica XVII, 49-98.

- Hald, M. 1980. Ancient Danish Textiles from Bogs and Burials. National Museum of Denmark.

- Roche-Bernard, G. 1993. Costumes et Textiles en Gaule Romaine. Editions Errance. Paris

- Roussin, L. A. 2001. Costume in Roman Palestine: Archaeological Remains and the Evidence from the Mishnah. In J. L. Sebesta & L. Bonfante (Eds) The World of Roman Costume. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Ruiz, J-C. No date. Mus¾e Bargoin Arch¾ologie Guide. Ville de Clermont-Ferrand.

- Wayland Barber, E. 1999. The Mummies of ¥ròmchi. Macmillan Publishers Ltd. London

- Wild, J. P. 1968. Clothing in the North-West Provinces of the Roman Empire. Bonner Jahrbòcher 68, 166-240.